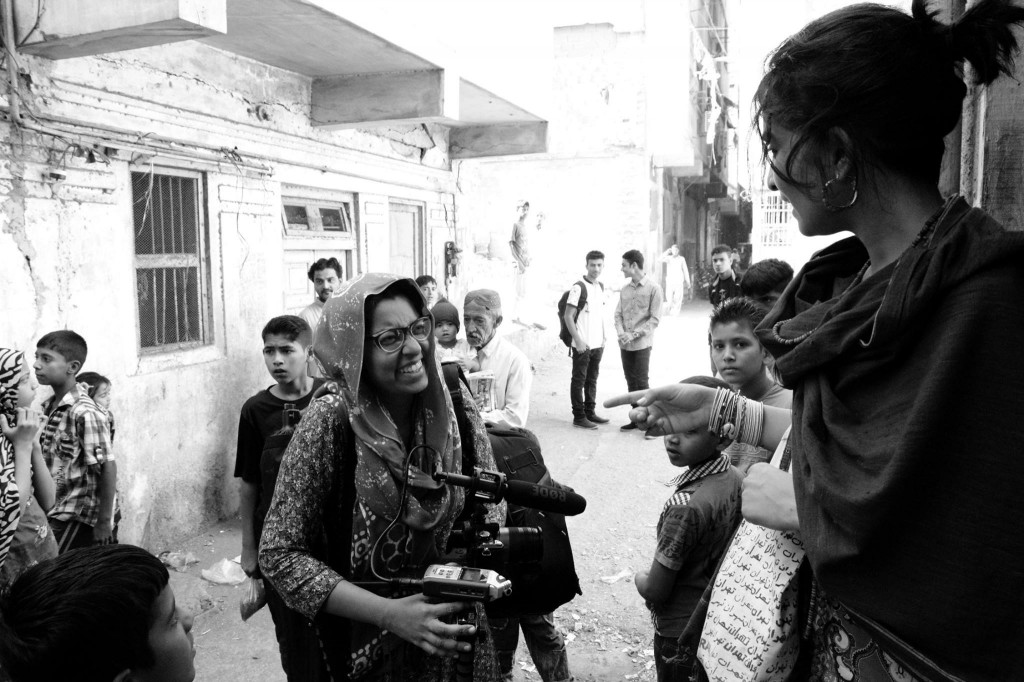

W4 had the pleasure of speaking with Haya Fatima Iqbal, the freelance documentary filmmaker, producer, and journalist — and recent winner of the Best Short Documentary Oscar for the incredibly powerful film, A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness, which she co-produced.

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

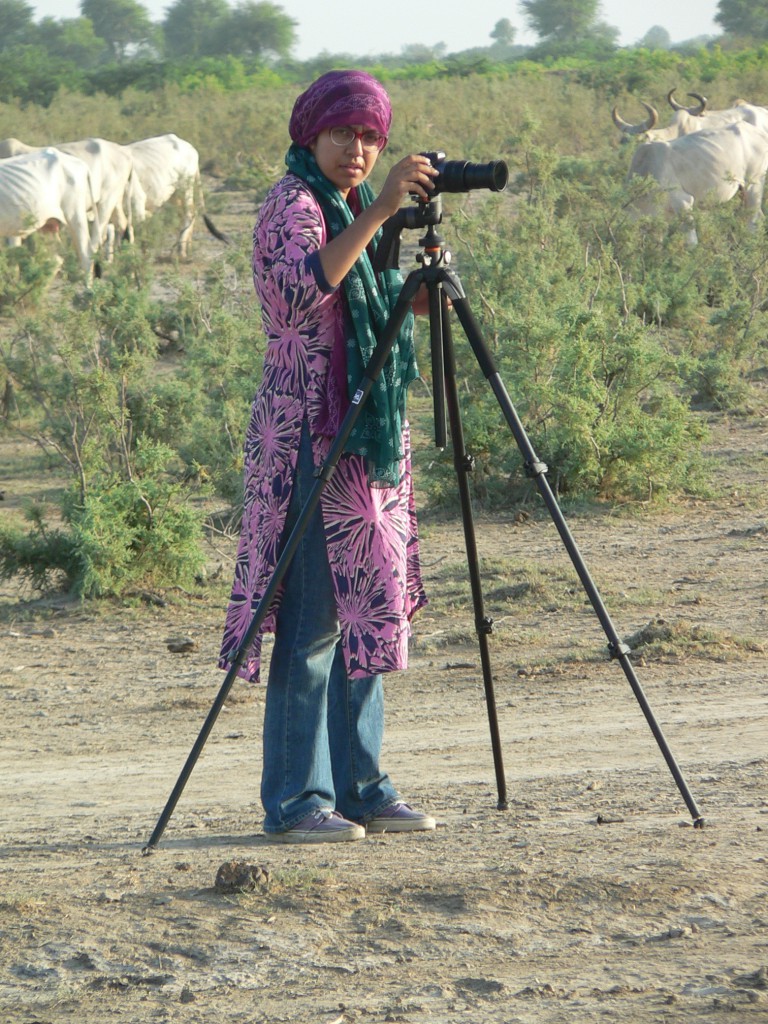

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

Please tell us about some of your recent work.

We filmed A Girl in the River about a year ago and receiving the Oscar for that was obviously amazing. Since then, I’ve been directing, shooting, and producing a web series (14 five-minute-long films commissioned by the Fulbright Commission in Pakistan) that follows the stories of 14 Fulbright alumni who studied in the U.S. and then came back to Pakistan to do things that are contributing to the country’s progress and development.

I got to travel all over the country to profile these people who are doing incredible work. Some who have studied theater have come back to do performance work and stand-up comedy. One young woman studied public health at Columbia and then came back and did part-time work at a non-profit organization. When she saw the on-the-ground conditions, she decided to learn healthcare skills and not just be the person who drafts policy. She ended up becoming a midwife herself and now she delivers babies every day! I’ve met many people like this. Crazy, generous souls.

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

What inspired you to start making documentary films?

After graduating from the University of Karachi I worked as a reporter at a local newspaper. They didn’t have any qualms about having a newcomer out in the field, so I learned a lot. As an undergraduate, I had developed an interest in video and I did internships at TV stations. I enjoyed shooting and liked the editing process, but I discovered that you only see a small part of the story because every TV news package has to be only a minute long, two minutes maximum. You just impart information and sometimes fail to illuminate the reasons why the people involved acted as they did. I felt that longer stories needed to be told, and in a more multi-layered way, so I went to do a Masters degree in documentary film-making at NYU.

With documentaries you can spend months or even years with people to really try to portray what the actuality is. But, obviously, documentary filmmaking comes with its own concerns and problems – the biggest is always the lack of funding. Few people want to invest in a project that will continue for years, especially when you don’t know what the outcome is going to be. Often documentary filmmakers have no fixed plan; they just see how things unfold.

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

What makes film such an effective way to capture an audience?

Locally, film has immense power because not everyone can read or write. In a country like Pakistan, print becomes something essentially limited to people with privilege, particularly when the national language is not understood by everyone. Television is still not available all across Pakistan, so there are areas where radio is the strongest medium. But the reach of TV is increasing every day: there’s always some place with a TV set and the whole community gathers there. Although video is still not the most prevalent way to communicate with people here, it is one of the most powerful. There are things that you can establish through film that you can’t in any other way.

Globally, things have much more power when they are filmed versus a print story. Many people don’t want to read a piece that’s over 400 words. With video, you’re not making anyone read, you’re just asking them to press PLAY. That’s where their job ends. It’s putting more responsibility on the filmmaker.

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

What part of your work do you consider to be the most important?

You first have to sense the story that you want to follow. Then you’ll find the best character. Even with the lowest-quality camera, you can have great success if you conduct a really powerful interview and ask the right questions, especially if you’re able to create a bond with your subjects even before conducting the interview, so that they’re willing to delve into the deeper details of their lives without feeling nervous or scared. Obviously, the way you film, the way you edit, the kind of action footage and extra footage you get of the interviewee are all very important, too. But the interview is the most powerful element. If the interview is weak, it won’t translate into something strong. That’s when you go and find another character for the same subject. You have to scout and search for people who can express themselves with a lot of passion.

Photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

Photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

How do you think making films can create positive change?

Sometimes as journalists and filmmakers our intrinsic job is to just tell the story. My first documentary (which I made as a student) was about ethnic-based violence stemming from political parties in the city of Karachi. They were bad years. Hundreds of people could be murdered within two or three days — then, the next day, you’d have to get up and go back to work. With ethnic violence the roots go so deep that a film can’t really have an immediate tangible impact. People don’t get up and promise that from that day on they’re not going to make racist jokes or mock ethnic stereotypes. They don’t immediately get involved in any sort of narrative that will end the cycle of violence. But such films can make people sit up in their seats and ask, ‘What has been happening?’

Other times, our task is to make people feel so invested in the issue that they get up and take action. A Girl in the River, was a film where the director made a huge effort and proposed legislation to the prime minister, who helped to ensure that the film was promoted and made clear that his party supported this legislation, which was for stricter punishment for those involved in honor killings.

Both kinds of impact count. Making people think about an issue is the first step towards greater positive change.

photo by Muhammad Hassan Motiwala

photo by Muhammad Hassan Motiwala

What are your future ambitions for your work?

My goal is to create films that make people think and make them ask about what’s been happening all this time around them . I’m exploring a number of big issues right now and I’m looking forward to some downtime so that I can think of various angles and the characters I can follow. I want to make films that can be shown in more grassroots situations, going to communities, residential areas, schools and religious schools, where people can watch with open minds and hearts, talk about how the film makes them feel, and think about how the average person is complicit in certain issues.

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

photo by Messum Aly Zaidi

How can people support your work?

Not everyone can raise funds for your film and that’s not something a filmmaker should expect. Documentary filmmaking can sometimes be very anonymous because we don’t appear in front of the camera, so people don’t know what a certain director is working on. Sometimes it’s helpful to just put it out there. Other filmmakers might be working in the same region on similar issues, and the more people you tell about your work, the more well-meaning filmmakers and journalists will send you messages of support or offer practical help or some of their contacts. Equally, personal networks can be invaluable for connecting filmmakers with people willing to work behind the scenes and help get the issue highlighted. Sometimes we filmmakers like to think we’re independent and don’t need help, but success really boils down to who is willing to work with you.

photo by Muhammad Hassan Motiwala

photo by Muhammad Hassan Motiwala

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I want to make people think. Online, you can be bombarded with so much information that you take it for granted. Journalists and filmmakers and other people contributing to web or print content are working day in, day out to inform people of what is actually happening. As consumers of information, we need to take a step back and contemplate the kind of sources we prefer — and often use, every day, for free. If you respect a certain journalist, source, or way of writing, think of ways you can offer support. How can you help those individuals and organizations to be seen?