« The world’s most dangerous country for women »: this is how Afghanistan is ranked in a study conducted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. High rates of maternal mortality, forced marriage, and female illiteracy all combine to make Afghanistan one of the worst places in the world for a woman to live. More than a decade after the fall of the Taliban, have women’s rights improved?

|

Chekeba Hachemi was born in Afghanistan. During the Soviet-Afghan War, when she was 11 years old, she left Afghanistan on foot and went to France, where she lived until she had completed her studies. After founding Afghanistan Libre, she travelled constantly between France and Afghanistan and in 2001 she became the first Afghan woman diplomat. Her most recent book, L’Insolente de Kaboul, recounts her personal history and offers insights into women’s living conditions in Afghanistan. |

In a September 2013 report, « Afghanistan, Ending Child Marriage and Domestic Violence », Human Rights Watch decries the still-widespread practice of forced marriage, which affects 70-80% of Afghan girls, with often disastrous consequences. Married too young, girls aged 15 to 19 are twice as likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth as women over 20 years of age. For girls aged 13 to 15, the risk is five times greater.

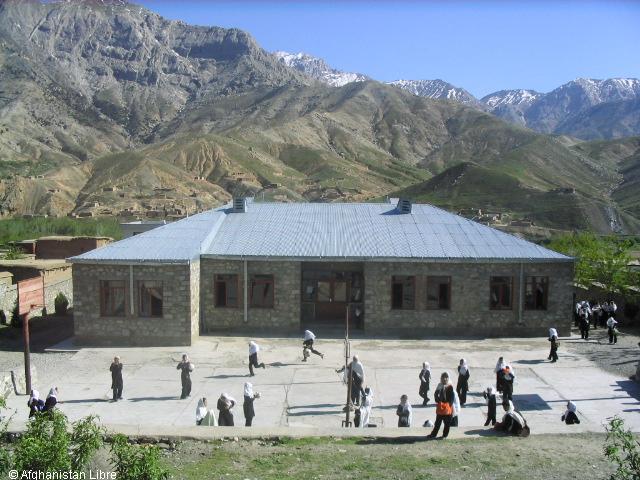

HRW’s observations are stark: Afghanistan has one of the world’s highest maternal mortality rates and « one Afghan woman dies every two hours because of pregnancy« . Fortunately, numerous groups are mobilizing to change this reality, and Afghanistan Libre (AL) is one of them. Founded in 1996 by Chekeba Hachemi, the Afghan-French association is based in the Paghman district, in Kabul’s periphery, and in Panjshir Valley. This mountainous region, with a Tajik-majority, was severely damaged by offensives led by Soviet troops and later by the Taliban.

Afghanistan Libre focuses its constructive efforts on several fronts, the most important of which is the building of high schools for girls. “Even if we have rights, as long as we don’t have access to education, we can’t defend ourselves,” Chekeba explains. As Liesl Gerntholtz, Director of Women’s Rights at HRW, notes, President Hamid Karzai’s signing of the law against domestic violence and child marriage has helped ensure a judicial frame, but practices have changed very little. This is the biggest challenge: enforcing laws that break with established customs and traditions.

Under these circumstances, AL’s efforts to support girls’ secondary education are vital: they work to protect girls’ human right to education; offer them a safe environment, free from the threat of violence; and enable them to become more financially independent. After finishing high school, AL’s girls can earn scholarships to study at university.

Educating girls also means equipping half the population with the necessary means to participate in the country’s economic development. Florent Caillibotte, currently head of the mission in Kabul, describes the program’s impact: “More and more girls pursue their studies and have the opportunity to get a job. Even if those jobs are still very gender-marked, for now, it is a huge step.”

The Afghan–French association is made up of several teams. On site, the expats work hand-in-hand with the Afghan team, while the French branch manages funding and accounting. Each mission begins with the building of a girls’ high school; next they set up a health education room (dedicated to mothers); then a library; and, finally, they establish a psycho-social support program to “help deal with the consequences of three decades of war”. Everything is organized around the high school space.

The Afghan–French association is made up of several teams. On site, the expats work hand-in-hand with the Afghan team, while the French branch manages funding and accounting. Each mission begins with the building of a girls’ high school; next they set up a health education room (dedicated to mothers); then a library; and, finally, they establish a psycho-social support program to “help deal with the consequences of three decades of war”. Everything is organized around the high school space.

“Our strength is that we truly work with the villagers”, Chekeba explains. “That’s why they support us and why our programs are perennial.” This local focus and the ability to work with direct and indirect recipients enables AL to target girls’ and mothers’ needs with great accuracy and implement carefully tailored solutions. This is exactly what happened in the health education program: in 2002, during a trip to one of the Panjshir villages, Chekeba found herself talking to a local woman who was evidently the first in her village to reach menopause. At that point, no one knew what it was.

Likewise, discussion is sometimes all it takes to solve what appears to be an intractable problem. When Afghanistan Libre offered to organize sports activities for the girls, a first in Afghanistan, the villagers could not reach a consensus of approval. When she spoke with the fathers, Chekeba understood their resistance: “The high school’s walls were not high enough, and they were afraid that their daughters could been seen while they moved. So, we increased the wall’s height—and then everyone agreed.”

Likewise, discussion is sometimes all it takes to solve what appears to be an intractable problem. When Afghanistan Libre offered to organize sports activities for the girls, a first in Afghanistan, the villagers could not reach a consensus of approval. When she spoke with the fathers, Chekeba understood their resistance: “The high school’s walls were not high enough, and they were afraid that their daughters could been seen while they moved. So, we increased the wall’s height—and then everyone agreed.”

In 2011, Afghanistan Libre was awarded the Prix des Droits de l’Homme de la République Française. Its pioneering efforts also include the publication (in collaboration with ELLE) of the only women’s magazine in Afghanistan, ROZ, which you can support via our platform.

Despite these achievements, the outlook of this pioneering organization is becoming less certain. The withdrawal of American troops and upcoming presidential elections have created fear of a resurgence in conservatism and a threat of backlash. Today, more than ever, Afghanistan Libre’s work is needed to maintain and build upon the country’s precious advances in girls’ and women’s rights.

© 2013, Women’s WorldWide Web